-

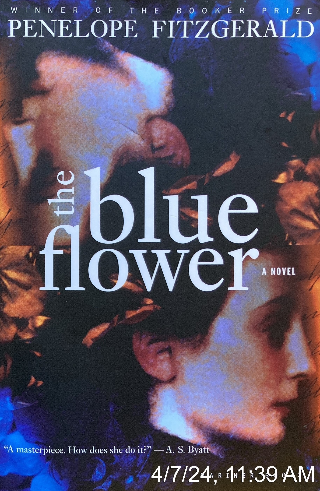

Penelope Fitzgerald, "The Blue Flower"책 읽는 즐거움 2024. 4. 8. 07:17

.

Penelope Fitzgerald, "The Blue Flower" (1995)

뉴욕 타임즈 서평 (by Michael Hofmann, Apr. 13, 1997)

몇 년 전에 사둔 이 책을 잊고 있다가 지지난 주 Kate Atkinson 소설 Transcription의 저자 노트에서 같은 영국 작가 Penelope Fitzgerald 의 소설 Human Voices를 언급한 걸 읽으면서 생각이 났다. 본문이 230쪽이 채 안 되는데, 처음 몇 쪽만 읽어도, 이래서 이 책을 걸작이라고 하는구나, 느낌이 들 거다. 위 서평이 잘 말해준다. 온라인으로 읽기가 좀 불편해 보이기도 해서, 서평의 좀 많은 부분을 인용한다:

These fugitive scraps of insight and information -- like single brushstrokes of vivid and true colors -- convey more reality than any amount of impasto description and research. In Ms. Fitzgerald's books you can breathe the air and taste the water, just as ''the Gaul'' (the nag, the hack) does in ... ''The Blue Flower''[: 아래 본문 인용 (p. 45)].

It is a quite astonishing book, a masterpiece, as a number of British critics have already said.... It is also her greatest triumph, as luminous and authentic a piece of imaginative writing about a writer, in this case a seminal German writer, as Georg Buchner's ''Lenz,'' Hugo von Hofmannsthal's ''Letter of Lord Chandos'' or Thomas Mann's tiny story about Schiller, ''Weary Hour'' -- three of the great glories of German literature.

Her subject is Novalis, a German Romantic poet and man of wider genius, who lived from 1772 to 1801 and combined, roughly, the intense flaring life of a Keats with the intellectual breadth of a Coleridge. Or rather it is Novalis before he became Novalis and was merely Friedrich von Hardenberg, or Fritz .... The novel covers the years from 1790 to 1797, years when he was a student of history, philosophy and law at the universities of Jena, Leipzig and Wittenberg, before he set out on his early professional life ....The book evokes his homelife as the oldest son in a large, vivacious and affectionate family in a ramshackle house in a small town in Saxony, his meeting with the 12-year-old Sophie von Kuhn in 1794, his unofficial engagement with her the following year, and her death two years later from tuberculosis.

It is hard to know where to begin to praise the book. First off, I can think of no better introduction to the Romantic era: its intellectual exaltation, its political ferment, its brilliant amateur self-scrutiny, its propensity for intense friendships and sibling relationships, its uncertain morals, its rumors and reputations and meetings, its innocence and its refusal of limits. Also, ''The Blue Flower'' is a wholly convincing account of that very difficult subject, genius.... Fritz's dissident understanding, his odd mixture of intellectual calm and excited curiosity (''Why not? Nonsense is only another language'') is latent, made clear in the exchanges with his brothers and sisters in a way that is beyond what any biographer could achieve. Things written by the historical Novalis arise here naturally and seamlessly from the character of Fritz -- for instance, ''We could not feel love for God Himself if He did not need our help.''

The quiddity of life in a remote place, at a remote time, is managed with characteristic brilliance by Ms. Fitzgerald: ''Even Tennstedt had its fair, specializing in Kesselfleisch -- the ears, snout and strips of fat from the pig's neck boiled with peppermint schnapps.'' Further, she uses tiny doses of German ... and of literally translated German expressions (''own-ness'' ...). That and a barely detectable abruptness in some phrasings are enough to move the reader back 200 years to the various Romes and Athenses of Saxony. Hundreds of pages of gothic type wouldn't have been able to do it.

And, of course, like the masterpiece it is, ''The Blue Flower'' ranges far beyond itself. It is an interrogation of life, love, purpose, experience and horizons, which has found its perfect vehicle in a few years from the pitifully short life of a German youth about to become a great poet -- one living in a period of intellectual and political upheaval, when even the prevailing medical orthodoxy ''held that to be alive was not a natural state.''

서두 글

"Novels arise out of the shortcomings of history."

F. von Hardenberg, later Novalis,

Fragmente und Studien, 1799-1800

본문 인용

Between Rippach and Lützen he stopped where a stream crossed the road, to let the Gaul have a drink, although the horse usually had to wait for until the end of the day. As Fritz loosened the girths, the Gaul breathed in enormously, as though he had scarcely known until that moment what air was. Fritz's valise. tied to the crupper, rose and fell with a sound like a drum on his broad quarters. Then, deflating little by little, he lowered his head to the water to find the warmest and muddiest part, sank his jaws to a line just below the nostrils, and began to drink with an alarming energy which he hads never displayed on the journey from Wittenberg. (p. 45)

She stood just inside the gate, listening to the shifting and creaking and strange repeated ticking which birds, in their restless half-sleep, make all night. They lodged in the great cherry tree, which produced two hundred pounds of fruit in a good summer, so that at first light they could start gorging themselves before the gardner's boy arrived. The cherries were almost black, but could still be distinguished from the mass of leaves, gently stirring although there seemed to be no wind. (p. 161)

Upstairs, Goethe takes the hardest chair, saying, with much charm, that poets thrive on discomfort. However, in another moment he is pacing up and down the little room.... Goether handily cuts the cake himself, and opens the bottle. He suggests sending down a glass of wine to the servant, which I agree to, although I can't see that he has done much to earn it. (p. 187)

'책 읽는 즐거움' 카테고리의 다른 글

David Eagleman, "Livewired" (0) 2024.05.16 N. Scott Momaday, "House Made of Dawn" (0) 2024.04.20 Nick Lane, "The Vital Question" (0) 2024.04.01 Kate Atkinson, "Transcription" (0) 2024.03.30 Paul Yoon, "The Hive and the Honey" (0) 2024.03.22